- Home

- Cormick, Craig;

The Years of the Wolf Page 12

The Years of the Wolf Read online

Page 12

Arno leans heavily onto his crutches. Feels he is suddenly much heavier and wearier than he has ever been before. Feels he needs to go back to his bunk for the day, like Horst does. Then he wishes he were able to go to the beach and swim. Wishes he had not had the run in with the guard. Wishes Herr Eckert hadn’t been murdered. Wishes this day was not going to be marked by any new changes.

“Peter, Klaus?”

Again. “Peter, Klaus?”

Arno closes his eyes, listening carefully.

The Commandant stands silently waiting for somebody to answer. Heads are slowly turned back and forward, looking for Herr Peter amongst them.

“Peter, Klaus?” Once more.

Still no answer. The Commandant beckons two of the guards over to him and then sends them into the cell blocks to conduct a quick search. The internees stand in the morning sun waiting. The Commandant refuses to progress further down his list until Herr Peter is located.

The guards come running back after a few minutes and shake their heads. The Commandant looks around in annoyance. He repeats the name a final time, “Peter, Klaus?” Still no answer.

He calls two more guards over to him. Now four men clump off in different directions around the compound. Into the wash house. Into the infirmary. Into the kitchen.

Arno looks about him. Internees are still glancing around, as if Klaus Peter might be somehow standing amongst them when he had not been there a moment ago. But nobody can see him. If they had to conjure him up they would create a professor of Romantic Literature, living and teaching in Singapore when the war had come for him. He was a thin man, slightly bald. He wrote poetry that he never shared with anybody and had asthma. And he had been one of the theatre troupe, and had played one of Venus’ maidens the night before.

The four soldiers soon return, one by one, and report to the Commandant, shaking their heads. He looks down at his lists of paper. Thinks hard for a moment and then calls out, “Who is Klaus Peter’s cell-mate?”

A man steps forward. Herr Klees. Once a manager for a shipping company who is now thought of as a skilled tailor. He has his shoulders back, standing to attention. The Commandant beckons him to come forward and he passes the list of names to the Sergeant. He then leads Herr Klees towards the guardhouse to question him.

“Piper, Wilhelm,” shouts the Sergeant in a voice that echoes loudly around the yard.

“Hier.”

They find Klaus Peter shortly after they have finally opened the prison gates for the day. One of the internees sees him and reports it to a guard. His body has been thrown onto the breakwater like a broken chunk of granite. The legs are gone where the sharks have reached them at high tide. The guards carry the bloody remains away and herd the internees back into the compound, locking the gates once more.

A few men, like Arno, who had reached the beach early, had also seen the remains of drag marks along the sand leading to the breakwater. Inside the prison rumours and supposition scuttle up and down the corridors. By lunchtime the stories say that

Herr Peter had been very depressed. He had been very drunk last night. He had been murdered. He had been thrown to the sharks, but they had not finished the job. He had left his cell late in the night. Only a guard could have carried his body out of the compound.

The internees look out through the high barred windows, at the khaki-clad men with rifles on the watchtowers. Only a guard! And the solid stone cells do not seem as secure as they had once felt.

In the early afternoon Arno makes his way over to the infirmary. The morning’s commotion had caused him to miss his daily session with Nurse Rosa, but he hopes she is still there. Hopes she might still massage his legs for him, and talk to him a little. But she is not there. Intern Meyer is minding the infirmary and looks very jumpy when Arno arrives. He smiles and tells Arno to come in and lie on the bed. Arno says it doesn’t matter. Says he has been looking for Nurse Rosa, and asks if intern Meyer knows where she is. “She’s not been in today,” he says. “And Doctor Hertz has gone into Kempsey with the Commandant. They have taken the remains of Herr Peter in the back of an army truck.” He shrugs a little, trying unsuccessfully to make it seem routine. “They have gone to see the officials there. To make out the death certificate, you know.”

Arno nods. He sits down and looks around the small room and tries to think of something to ask intern Meyer. But he doesn’t know him very well. Yet it is Meyer who first asks a question, “Do you get on well with Nurse Rosa?”

“Yes,” says Arno. “Very well.”

“Oh?” asks intern Meyer.

“We have lots of conversations, you know.”

Intern Meyer nods. “She has been massaging your legs for almost two years now, ja?”

Arno thinks carefully and says, “It makes nearly 300 hours.”

“So long?”

“Yes. Put together it would be over 12 full days.”

Intern Meyer smiles. “You are a very precise person.”

Arno nods. “There is much time for precision here.”

“You are also a very lucky person,” says Meyer.

Arno looks down at his crutches and doesn’t say anything.

“I think she likes you,” says intern Meyer.

Arno can feel a warm blush rising up his neck. He looks down at his watch. 2.18. Looks back up at the bare stone wall. “Do you think so?”

“Of course.”

Arno is about to say that he thinks she likes Doctor Hertz more, but he doesn’t want that thought confirmed. He just sits there and lets the heat continue to rise around his collar, feeling the burning pleasure of it.

Then suddenly a dark shape fills the door. Arno looks up quickly, thinking it might be the guard again who had threatened him. But it is an internee. A thick-set man named Smitz. One of the athletes. One of the boxing club. He rubs his large hands together and says, “I am looking for Nurse Rosa.”

“She is not here,” says intern Meyer.

Smitz looks at both Arno and Meyer. Sniffs deeply. Then turns his head a little and spits outside. “Well you two boys tell her when she comes back that I came looking for her. Tell her that I want a special appointment with her.” He steps closer into the room and puts his hands on his hips. “You understand me?”

Neither Arno nor intern Meyer reply.

“You tell her that?”

“She is not here,” says intern Meyer again. Smitz takes a step closer towards him. “But you must tell her.” He says it quietly, so his meaning is very clear.

“She might be back tomorrow,” intern Meyer says. “When the doctor is back.”

Smitz takes a step back. Then says, “I’m not afraid of the doctor.”

“Can I tell him that too?” asks intern Meyer. And Smitz’s hand suddenly strikes out, hitting him in the chest. The blow knocks him back against the wall and intern Meyer stays there, hugging the stone for support. Then Smitz sniffs again. He rolls spit around in his mouth, then turns to Arno. “Better look after your friend,” he says. “He could do with some nursing.”

“That was an excellent attack,” Arno says. “You are wasted here and should be in the trenches in France.”

He can see Herr Smitz trying to decide if that is a compliment or an insult and then sees the man shrug, turn and steps back outside. He spits noisily again and is gone.

“Are you all right?” Arno asks Intern Meyer.

But he doesn’t turn from the wall. Just says, “I’ll be okay. Please leave.”

Arno finds Herr Herausgeber in the small cell that is his newspaper office. He is very disturbed by the death of Herr Peter, and tells Arno that he is sure there will be a lot of trouble because of it. He has been thinking of writing something in his newspaper about it, but he is not sure what to say.

“Death is a very difficult topic to handle,” he tells Arno. “You can craft your words carefully, thin

king you have them just right, but you find that when your readers get them they have suddenly changed and taken on new meanings.” He picks up a sheet of paper with a single column of type on it, and holds the words up to the light to examine them.

And Arno is filled with a sudden need to tell him what he knows about Herr Eckert and Herr Peter, and he knows both men were murdered in some way, and that the doctor is aware of it. But Herr Herausgeber is not a good listener and is already talking again. “There will be trouble for all of us because of this, you mark my words,” he says, with his head bent down over columns of type laid out on a small desk before him. He has scissors and paste and is moving the words around before him. Creating an article. Creating his own versions of realities. “The Commandant should put a stop to it at once!” he says.

“Put a stop to what?” asks Arno.

Herr Herausgeber turns his head a little to regard Arno. “The alcohol smuggling of course.”

Arno shakes his head a little. “What?” he asks.

Now Herr Herausgeber turns fully to regard him. “Don’t tell me you don’t know?” he asks.

“No,” says Arno.

Herr Herausgeber sighs heavily. “You are the most amazing boy. You see so many things and yet you must be the only person in the camp, including the Commandant, who does not know. For months the guards have been smuggling alcohol in for some of the men. It is stored in the watchtowers and they make their transactions in secret in the night. They pay good money for it. But a high price. Too high a price it now seems.”

“Do you mean Herr Peter was involved in it?”

“So it appears, although I had believed it was restricted to the members of the Wolf Pack.”

Again Arno shakes his head a little. “What?” he asks.

Herr Herausgeber turns back to his words. “And don’t try and tell me you didn’t know of the Wolf Pack in the camp.”

Arno doesn’t even try to reply. Everybody talks about the gangs that are active in the large internment camps at Holsworthy near Sydney, organising sedition and causing trouble for the guards whenever they could. But he had no idea they had a presence here. And Arno has that sudden giddy feeling again, that he has emerged from the stone of the walls into a different world to the one he had left.

But then it all becomes suddenly clear to him. It is Herr von Krupp and the athletics club, he thinks. They are the Wolf Pack. That explains his power over the other men. But the doctor? What is his influence? “Who is the leader?” he asks Herr Herausgeber.

But the editor does not reply. Instead he lifts up a sheet of text and says, “Wait until the men read this. The German forces have made great advances on the Western Front. They will overrun the Allies’ lines soon. Push them right out of France.”

Arno does not need to read it. He has read it all before. Every issue of Welt am Montag predicts that the great last push is about to take place. And yet the war goes on—without the word war ever being mentioned.

“They will push them right back to England,” he says. “Then the German navy will invade England while the airships bomb London. They will conquer the British army and then they will return to the Pacific Ocean. You mark my words, one morning you will walk out the front gates and you will see a dozen ships out there on the horizon, steaming towards the headland here. And we will stream out the gates to welcome them.”

“Why was Herr Peter killed?” Arno asks him.

Herr Herausgeber lays down the copy he is working on and turns to look at Arno. “Because the guards fear us. Because they know we shall defeat them. Because they know one day those ships will appear on the horizon. Because they know that Germany is far stronger than they pretend.” And he waves his hand dismissively at the pile of Australian newspapers stacked on a chair. Some of the guards sell him old papers to search through for stories for Welt am Montag. Arno picks up the top copy and looks at it. The Australians are still fighting over conscription he sees—as if there isn’t anything more important to fight over. The other stories are of allied victories in France. German troops demoralised. British war production at an all-time high.

There are photographs from the front. Brave Tommies standing over German trenches waving a British flag. Dead German soldiers lying in the mud. Limbs missing. Blood oozing into the soil. Arno looks at the faces of the dead men. Dark and lifeless. Like Herr Peter. Looks at the faces of the Tommies. Grinning bad teeth. Wild eyes. Mad looking. He wonders if the German troops had looked as mad before they were killed.

Herr Herausgeber looks around and sees Arno is absorbed in the newspapers. “Don’t believe anything you read in them,” he says quickly. “It’s all propaganda. Designed to keep morale high. Designed to make them hate us more.”

“Do you think that is why the people over at South West Rocks hate us so much?” asks Arno. “Why they smash our huts? Because they are told to?”

Herr Herausgeber looks back to his words. Cuts out some more and rearranges them. “Yes and no,” he says. “They don’t only hate us because of the propaganda and the thoughts of their family members who are fighting and being wounded or killed in the war—even though they never stop to think that we too have family members fighting and dying in the war. They also hate us because of the truth of this camp.”

“What truth is that?” asks Arno.

“The truth that we get three meals a day. Meat every day. Sun shine and exercise.”

“I don’t understand,” says Arno. “What do you mean?”

“Do you know how their people are being treated in Germany?” he asks Arno. “The prisoners there. Do you think they get meat to eat even once a week? Do you suppose they even get fed well? Or regular exercise? Did you know that there are over one million internees and prisoners in Germany? Living in conditions that make Holsworthy seem pleasant.”

Arno hadn’t thought of it before. But he knows Herr Herausgeber is right. And he knows the people of South West Rocks know it too, and hate the Germans in the old prison for their sheltered lifestyle. And then he has a sudden image in his mind of the body of Herr Peter dashed onto the hard rocks of the breakwater and the local fisherman Gavin Hooks and his mates standing over him. Holding a British flag. Smiling. Wild eyes. Mad looking.

Arno puts the newspaper down and turns to look at the photos stuck all over the stone walls. Internees swimming on the beach. Internees queued up for breakfast. Men playing tennis. Men sitting on the balcony of a small cafe. Men on the stage of the theatre. Men waving happily at the camera. It is more than just half the world removed from the war, he thinks.

“If you believe even a small bit of what you read in the Australian newspapers,” Herr Herausgeber says, “Allied internees are living in labour camps.”

But Arno isn’t listening any more. His attention has been caught by one photograph pinned up on the editor’s wall. Amongst the many photographs there is one he has never seen before—a shot of Hans Eckert dressed like a woman, smiling seductively at the camera. One strap of his or her dress is hanging off the shoulder and one hand is cupped under a breast. And he notes there is a new backdrop of a ship in the background, sailing towards her—or him.

Doctor Hertz returns with the Commandant in the late afternoon. He is met in the dining hall by a delegation of internees led by Herr von Krupp. They talk together for a short time and then the doctor leads them back to see the Commandant. Internees sit in the dining hall or stand around in the compound near the gate, waiting for them to emerge. They are well practised at waiting.

And leaving Herr Herausgeber’s office Arno Friedrich limps out into the yard and sees Nurse Rosa is there, sitting on a wooden chair outside the infirmary building. She must have just arrived, he thinks. He watches her lean back against the wall, her eyes closed, her head tilted up to the sun. Arno draws back a little and stares around. The yard there is empty. He looks back to her. Sees her arms lay relaxed in her lap, pal

ms upwards, and her legs are crossed at the feet, with her long white skirt lifted just a little to let the sun onto her legs. The sun shines so brightly off her white uniform that it appears to give an aura to her body. This is how the great painters would have envisaged apparitions of angels, he thinks. Just like this.

He wishes he were standing closer to her, but doesn’t want to disturb her. He has never seen her looking so at ease. So unguarded. So given over to pleasure. She smiles, moving her head a little, as the warm sun plays around her neck.

Arno moves his head a little too. Just the way she has. Smiles too. Wishes again he were closer. Sitting next to her. Sharing her pleasure. Watching her face up close. Studying that slight smile upon her lips and examining the set of her arms and legs. Holding his just the same. Perhaps even holding out his hand, so that she would take it in hers. Those long fingers settling in his own like a fragile bird’s wing, he thinks. He will write this scene in his diary, he determines. Retell the story so that he is sitting beside her.

There is a sudden noise behind him and he turns to see three men walking out of the dining hall. They are upon him quickly and noisily walk past, towards the Commandant’s office, where most of the men have gathered. Arno turns back towards Nurse Rosa, but she has flown. Gone like a startled bird.

Doctor Hertz and the delegation have negotiated with the Commandant for over an hour and emerged triumphant, with permission to erect a memorial to their dead comrades on a high point on the headland, looking out to sea. The word spreads around the compound quickly, gathering enthusiasm. There is an impromptu meeting in the hall and some men volunteer to cart stone from the old quarry used by the convicts, others begin sketching designs. Those with building experience quickly begin debating the best way to build the structure, and others begin drafting the words to go onto the tombstones.

Doctor Hertz is glad of the distraction. The men are so obsessed with the memorial that nobody has asked him what was the cause of Herr Peter’s death. Nobody has asked whether he was dead before the sharks got to him, and nobody has asked him how Herr Peter might have gotten outside the prison walls. But he has practiced his answer anyway. “Causes of death are not always what they seem. We should wait for the final results of the full examination.”

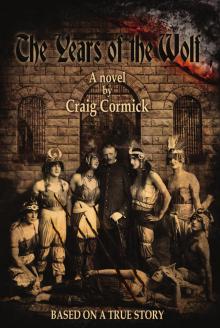

The Years of the Wolf

The Years of the Wolf