- Home

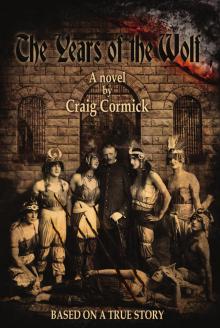

- Cormick, Craig;

The Years of the Wolf Page 10

The Years of the Wolf Read online

Page 10

As soon as he has heard the news Herr Herausgeber comes out to inspect the damage. He walks amongst the ruins with his notebook held out before him. “They are barbarians,” he says aloud. “They are worse than barbarians. This is senseless vandalism. What have we ever done to offend them?”

Some men gather around him and mutter that the raiding party must have come through the dark forest, or else arrived by boat in the night, but either way the guards must have known they were coming. Must have seen something. Must have turned their heads away.

Then Captain Eaton appears, surrounded by a small handful of guards. He too inspects the damage. He shakes his head and tells the internees around him that he will ensure that the matter is taken up with the authorities in South West Rocks. “I will make sure that all efforts are made to apprehend the guilty parties,” he tells the internees. “Such actions cannot be condoned.”

The men listen to him respectfully. Some then go back to their cells to sit in darkness while others continue rebuilding their village—but both are certain that nothing else will be done about this. They are, after all, enemy aliens. They have affronted and threatened the local population by being German, and by being here. And they have no control over either.

Arno watches those men who have stayed behind go about their work trying to restore walls and windows. They scrub at the blood and mend broken supports, but he sees that they will never really be able to recreate the fantasy world they had constructed. Not now that it has been torn down and shown for what it really is. He also knows that Herr Herausgeber will run a large story about this in Welt Am Montag, deploring the destruction and lamenting that they are surrounded by hostile barbarians. But never once will he state that the war—that unspoken word—has finally crept right up to their isolated prison walls.

It is 11.05 by Arno’s watch and Nurse Rosa has not come. He lies on the bed in the infirmary, looking down between his legs, imagining he can see her there, holding his feet. Pressing them against her strong thighs. Smiling to him. Turning them first one way. And then another. He wonders what has caused her to be late? Wonders how high the anti-German feeling in South West Rocks has grown? Wonders if they are stopping her from coming?

He props himself up on his elbows and looks around the small infirmary. It is empty again today. Those still recovering from the fight prefer to do it in their own cells. This room does not feel enough like an actual hospital room to encourage men to stay. It feels too much like a prison room. The cold stone walls. The high barred windows. The eternal quiet.

He lies back down and closes his eyes. If she is not coming today, he will recreate her in his mind before Doctor Hertz arrives to twist and bend his feet painfully. First, he imagines the whiteness of her uniform. The stiff starched material. Then her auburn hair, tied up neatly beneath her red cap. Then the shape of her face. The curve of her cheeks and nose. The shape of her eyes and lips. Then her neck, plunging down deeply beneath the uniform to her shoulders and breasts. He thinks carefully of the hidden curves of them. And the many secrets of her past that she also hides. He wonders what stories she could tell him if she chose to, as she massages her legs feet. Her hands have hold of one of his feet now, lifting it from the bed, working the muscles and tendons in it, rubbing her fingers over the skin firmly as she moves it one way and then the other, shaping it and straightening it.

He opens his eyes and sees her sitting there, holding one foot, looking down at him. “Guten Morgen,” she says.

“Guten Tag,” he replies with a smile.

She smiles too. Just a little.

“You’re late,” he says.

“Ja.” Now no smile.

“I thought something might have happened?”

“No.” She puts his foot down and lifts the other. Looks past him. At the stone prison wall.

She is thinking of something far away, he thinks. Or somebody far away. And he wonders if she has a sweetheart. Somebody who is away at the war. Somebody who is fighting the Germans. Being shot at by them. How does that make her feel about working here, he wonders? And he wishes, not for the first time, that he could share her dreams and know what her fears and anxieties were. But also the things that brought her the most joy.

“Are you thinking of somebody?” he asks, stepping cautiously into no man’s land.

“What?” she asks, looking back between his legs at him.

It is harder to ask the second time. “Are you thinking of somebody?” he says it again slowly.

“No,” she says. “Just me.” Still distant.

Arno nods. Wishes to bring her back to the present. Back to him. “Did you see what happened outside the walls?” he asks.

“Yes.” She stops and puts his foot down. Looks at him coldly. Arno knows he has said the wrong thing and tries to make light of it. “A fierce storm might have done as much.”

“No,” she says, anger in her voice now. “It was done by men! Those angry ignorant hate-filled men!”

She puts her fist into her mouth, as if to stop anything emerging, then turns away from him.

Arno is searching for the words to make it alright, but he has none. He has not enough experience with women to really know where to begin. And when Doctor Hertz comes in and he sees Nurse Rosa is upset, Arno can only watch the easy way he goes to her and puts one hand on her arm. The other around her waist. He leads her to his office and sits her in a small chair there and pats her gently on the shoulder. Arno watches in fascination. Is it really so easy to reach out and touch a woman? he thinks. He can no longer remember.

Then Doctor Hertz closes the door and comes over to Arno. He looks up through his legs at the doctor and tells him, “We were just talking.”

Doctor Hertz picks up one of his feet. Twists it sharply one way. Then twists it the other. Arno clamps his teeth together as Doctor Hertz says, “Talking sometimes causes pain too.”

Herr Dubotzki is sitting in the dark in a small cell with the door locked tightly. He is staring at a blank sheet in front of him, as an image slowly starts to form. He moves the paper a little. Lets the developer run over it. Stares as the first shapes start to appear. A dark outline. Filling slowly. Then the soft grey of a face appearing. He watches carefully. He does not need a timer for this as he knows from experience when the print is ready. He watches as the face slowly solidifies, like coming towards him from a bright light, or out of the mist. The eyes are taking shape now, though the rest of the face is obscured by a veil. Now the detail of the figure’s clothes are clearer, as are the curves of the arms and the breasts and the pattern of the dress.

He smiles and takes the print out of the developer tray, brings it up close to his face for an instant and then lowers it to the fixer. He has it. Has captured the tones and the look on Pandora’s face forever.

He watches her floating under the fixer for some time and then lifts her out. He places her in water and lets her bathe in it. Then he lifts her out to dry. He admires her a moment and then reaches for another sheet of paper. It is like printing money, he thinks.

Arno is making his way around the compound, filling in time before lunch. He misses his morning’s swim, but has little desire to go outside again and see the ruins there nor the bloodied whale remains on the beach. He has tried to find somewhere else to go other than his cell, while trying not to get caught up in the activities of the internees. He is feeling dislocated today, like he is on the edge of slipping into a dream, or a vision, as if the world made stone around him is not solid at all—but something he could pass through into another world.

The past, maybe. Or the future? Or another version of the present? It feels as if he could press up against the chill granite walls and pass right into them. Move his body through the chill stone and come out the other side in a world where Herr Eckert had never been murdered. Where the locals had not attacked the prison and destroyed their make-believe village. Where ev

en if the world was still at war, it would be kept far away from this little corner of the world.

English language classes are being held in the hall, and they won’t be out of there for another fifteen minutes or more, according to his watch. If he gets too close, he knows, they will call him in to take part, as his English is better than that of most of the internees. He has gone some days and made up nonsense words like bomblebee and discomspute, and insisted they were real. But he has no interest in talking today.

He moves towards the washrooms and stops. Some of the members of the athletics club are showering and standing around in the sun there, puffing and panting. Their faces are red and sweaty and they grin at each other and laugh, mock boxing and slapping at each other’s bare skin. They have been playing team sports. They are great advocates of team sports. It might have been football today—or tennis. They will play any sport except cricket. That is what the guards play. The club members never seem to tire of setting up a playing field, laying down the rules, carefully going through all the motions of training and rehearsals, and then attacking each other with great gusto. The actual game doesn’t matter—it is only one part of the excitement.

He watches the men, bouncing on their strong legs and flexing their arm muscles for each other. At times they mock him for being a cripple and he responds by telling them that he won’t take them with him when he escapes from the prison.

And then he wonders how much strength does a man need to kill another? Do you need to be an athlete, treating the death fight like a contest? The strong overcoming the weak? He has strong enough arms, he thinks. He leans forward a little onto his crutches, taking all the weight off his feet, holding himself up on his arms. If he were quick he could do it. If he were backed up against a wall, perhaps. A quick stab or thrust. That was all it took, surely. Doctor Hertz would know, he thinks. He lowers himself back onto his legs. Takes the weight off his arms now and lets his feet hold his weight. Then he ponders the mystery of why the doctor is covering up the killing? Is it just to protect morale, or something else?

He looks at the members of the athletics club again and wonders at the possibility of a world so different that he might have to defend himself from them. Had to fight them. He tries to imagine himself facing any one of them. Tries to imagine stabbing at their strong muscular bodies. But he feels he would never do it. He has a sudden understanding that killing is not all about strength of body, it is more about strength of hate.

He lowers his weight back onto the crutches. Perhaps the doctor isn’t involved in the killing, he thinks. Surely there is nobody he hates. He is the most respected of all the inmates. He is the one the Commandant turns to when he needs to discuss the prisoners’ welfare. And he is the one they all choose to take their concerns and complaints to the Commandant for them. But, he thinks, moving his body weight back to his feet again, like he is weighing up an argument, he is also the one who knows the most about death.

He turns and limps back across the yard, towards the infirmary. He stops and leans against the wall there. Touches the stone. Closes his eyes and tries to feel the world within. The worlds beyond. But it is only stone. And the doctor is a good man. A man who will keep his word to him and fix his feet one day after the war.

He turns again to go back across the yard, but as he does so a guard comes out of the infirmary, carrying boxes. He trips on one of Arno’s outstretched crutches and falls heavily to the ground. He is back on his feet before Arno can even mutter an apology. “Bloody Hun!” he says. He dusts his uniform a little, and then steps up close—really close—and pokes Arno in the chest with one finger. “Would you like to try that again? Face to face with me?”

Arno stares at him as if he does not fully understand the guard’s words, and tries to back away a little. But the guard follows him and Arno sees that one side of the man’s face is badly scared with an angry red welt. “Come on,” he says. “A coward are you?” And he pushes Arno so that he nearly tips over, but he waves his crutch around to stop him falling. The guard’s eyes follow it carefully. Wary of it. Then he smiles, as if he has been challenged. He lifts his fists up and stares at Arno with hate in his eyes.

Arno shakes his head a little. “No,” he says, but the guard is not interested in what he says.

“Hun bastard!” the guard says.

Arno wonders if the man would kill him if he had a knife in his hand. If it were night and he had come across him in the dark. If he has in fact already merged into the stone of the walls and come out in a different version of his world, where he is no longer so certain he will survive it.

“Enough!”

The guard turns.

Doctor Hertz is standing in the door of the infirmary. His voice sharp and abrupt. “It was an accident,” says the doctor. “Leave the boy be.”

The guard jerks his chin around a little, as if adjusting it, then gathers up his boxes and walks off to the main gate.

“Thank you,” says Arno, and thinks to himself, I can survive this too.

The doctor just shrugs his shoulders. “There is enough fighting in the world already,” he says, and goes back inside the infirmary.

Private Simpson stands in the watchtower breathing slowly and heavily. He is bored. Too many long afternoons where not much ever seems to happen have gotten into his blood. Even the novelty of the whale corpse and the destruction of the Hun’s playhouses has worn off. He looks down to the whale’s carcass and sees the red-stained sand and the dark circling shapes of the sharks there. He has watched them overly-long, picking on the remains there, and is now sickened by the sight of them. The leftovers of the whale corpse and all that blood reminds him too much of the western front.

He turns and looks into the prison yard instead. The internees are bored too. He can see that easily enough. These Germans are bored with internment as much as he is bored with guarding them. At the front every day had seemed a lifetime of hell, but here it is too much like living in limbo—days fading into weeks into months.

He wishes he was on night duty. It is easier in a way. You could have a smoke and a drink and nobody could see you. And you could even sneak away from the tower for a bit when you had to. Anything interesting around here happened at night. He knows that sure enough. The night was a little dangerous and he likes that.

He sighs heavily. Plays the game where he is a sniper, imagining his is picking the internees off one by one with his Lee Enfield as they ran around the prison yard like chooks with a fox amongst them. He smiles. Then he turns and looks out northwards over the breakwater, and thinks of those convicts who laboured away on it in the last century. It would have been a bugger of a job guarding them, he thinks. Murderers and thieves. But it would have been more lively than guarding these dozy Huns. He follows the direction of the breakwater and for the first time notices that if they had kept building it, and not stopped, they would have ended up reaching Freedom Island to the north west of the headland.

He puts his hands up around his head, and shades his eyes, so that he can’t see the bloodstained beach. So he can’t see the prison. And he stares along the direction of the breakwater, towards the distant green trees of Freedom Island.

It is sundown and Arno Friedrich stands under the southwest watchtower leaning against the granite stone, arms out wide, staring up at the sky, watching the colour go out of the world. He feels the darkness descending upon him like a mantle. He stands there as the first stars come out, and he thinks he would like to see the whole sky full of stars for once, stretching from horizon to horizon and unobstructed by tall prison walls.

And he feels a touch of menace stirring within the walls, as if a dream or nightmare within is striving to escape. He stays by the wall for some time, as the feeling fades, and then he grips his crutches tightly and begins making his way around the prison. He goes along past the cell blocks and hears an argument coming out of one cell. He tries to make out which b

arred window cell it is coming from. Tries to make out the words. But all he can distinguish are the dark edges of anger in the voices.

He tilts his head back. Discerns it is coming from a second floor cell. Perhaps two cell mates, having forgotten that if you could not talk without conflict then it is better not to talk at all. He stands there and listens to the anger grow softer and then fade away until all he can hear is the low rumble of the distant grumbling surf on the breakwater.

Camaraderie makes for good comrades, Arno thinks, repeating the camp motto, and he continues on. Then he stops. He had felt something. Like swimming through a cold current in the ocean. He takes one small step backwards and then looks around. Listens. There is a soft clink behind him. He presses close to the wall and peers into the darkness. Listens for the sound again. It was something like the sound of a metal knife on stone. Then he hears it again. Much softer. Higher up. As if the noise is floating away into the sky.

He stays where he is and listens carefully. Thinks of the guard who wanted to fight him. Wonders what he will do if somebody confronts him in the darkness? Wonders if he could defend himself? Wonders if he imaginings are running away from him?

He turns and takes a slow and careful step forward. Then stops and listens again. Nothing. Then another slow step forward. He has just about convinced himself it was nothing but a random sound amplified by his imagination, when he hears the footsteps. Quite close. He turns his head as the figure reaches out and grabs him. He feels his heart leap out of his mouth. But a heavy hand clamps over his lips. A face is close to his own. Eyes staring at him hard.

The Years of the Wolf

The Years of the Wolf